Cal senior to publish study on headers

Publishing a scientific study is no easy feat. Publishing a scientific study while in high school is even more remarkable.

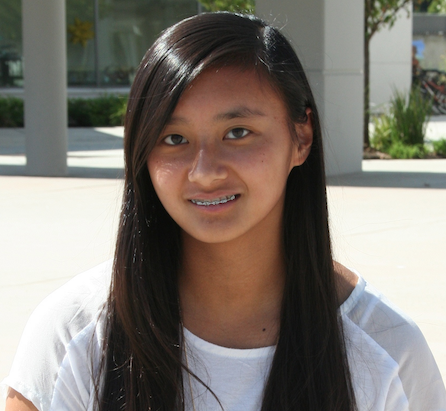

But that’s exactly what senior Radhika Balagopal is about to accomplish.

After reading a study published in February 2014 by Dr. Anne Sereno, a professor of neurobiology and anatomy at University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Balagopal contacted the professor with the hope of combining her two passions: soccer and science.

Sereno’s study, conducted with a group of high school soccer players and a group of non-soccer players, was one of the first to attribute short-term brain damage, in terms of reflexes, to heading the soccer ball, motivating Balagopal to research the long-term effects.

“In soccer, heading the ball is a mandatory thing in the game,” said Balagopal, who has played for Cal’s varsity team since her sophomore year. “But heading the ball hurts a lot. I’ve seen so many of my teammates have concussions and erratic moods, often causing their grades to drop.

“A header is painful, disorienting, and a ticking concussion time-bomb,” she said.

Cal’s women’s varsity soccer coach Lee Munson also testifies to the unfortunate necessity of heading the soccer ball during games for both defensive and offensive strategy.

“Heading the ball is a huge factor,” said Munson. “If you don’t head the ball at the varsity level, you won’t be able to play. For the guys, some players can kick the ball up 50 to 60 miles an hour. Think about what that’s doing to your head, and your brain.”

But no study has conclusively linked heading the ball to lasting brain damage.

Sereno’s previous study, however, found that while soccer players, as opposed to non-soccer players, displayed similar results on direct, stimulus-driven, or reflexive point responses, heading the ball does have noticeable short-term effects.

“[The soccer players] showed small but significant slowing compared to controls on indirect, goal-driven, or voluntary point responses, and [the study found] that this performance slowing was correlated or marginally correlated to number of headers, number of hours of soccer per week, and years of soccer experience,” said Sereno.

Balagopal’s study therefore seeks to compare soccer players to their own baseline to study further, lasting effects.

“Concussions are one way to measure [damage], but the question is if there is a long term-effect,” said Balagopal.

Balagopal has worked with Sereno and PhD graduate Stuart Red to study these effects through an iPad application developed by Sereno and her team at the university. The study has yet to be published, but Balagopal is hopeful that it will be by June. Where the study will be published also has yet to be determined. Preliminary analysis suggests that heading the ball is highly significant.

Balagopal conducted the study with Sereno and Red by monitoring her teammates’ reflexes. With her teammates’ consent, as well as Munson’s and assistant coach Amanda Heinz’s support, the iPad application was instrumental in testing pro-point, or voluntary, reflexes, and anti-point, involuntary reflexes before and after practice.

“It tested cognitive skills,” said senior Kara Guse, a former Cal soccer player who participated in the study. “It was simple, but it could generate a lot information about how the brain reacts.”

Senior Rachelle Herring also found the study very relevant.

“I got a concussion during the study, so it was interesting,” said Herring.

The study is particularly significant because of the high rate of concussions in girls’ soccer. In America, concussion rates in girls’ soccer are second only to football, which begs the question, what are the actual effects? The study also resonates with Balagopal personally.

When she was younger, her father, who used to be her coach, had always advised her against headers in a game setting.

“I told her not to head the ball based on what I had read on the dangers of heading the ball [at a young age],” said her father Balagopal Mayampurath.

If headers are not done correctly, underdeveloped neck and skull muscles could leave the brain susceptible to injury, said Mayampurath.

The topic of the study itself, soccer, is also highly important to Balagopal.

“Soccer is my life,” said Balagopal. “I’ve been living and breathing it.”

Balagopal has played soccer for 13 years.

But Balagopal stresses that the study was a team effort.

“None of this would have been possible if it weren’t for Coach Lee and Coach Amanda who really pushed my teammates to participate,” said Balagopal. “They both gave me tremendous support in my project.”

She is also appreciative of Red, Sereno and her teammates, who came early to practice and stayed late to take the test.

“It was a huge learning experience just talking to someone so qualified and learning from [Sereno] and Stuart,” said Balagopal.

Statisticians, scientists, and many others also collaborated to compile and analyze data.

“It’s a team effort where different people from different fields work together,” said Balagopal. “It’s so interdisciplinary.”

Balagopal would like to continue the study in the future to further study the long-term effects, but hopes that her most recent study can highlight the dangers of heading the ball for many others. She will also continue to test her teammates this year.

“To be a part of something this big is a real honor, especially because it has so much to do with my life,” said Balagopal. “On the field, we say, ‘I got your back’, but now off the field I can help them too.”