Holocaust survivor talks on campus

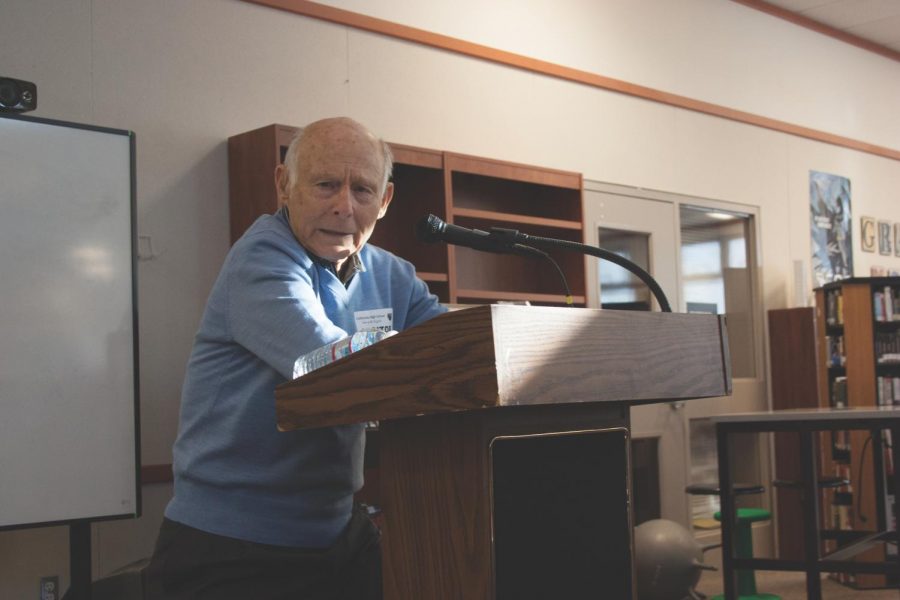

Holocaust survivor and San Ramon resident Bernie Rosner speaks to students at Cal High about his experiences at the Auschwitz and Mauthausen concentration camps. He focused his speech on the resilience of the human spirit.

Emotions ran high as Holocaust survivor and San Ramon resident Bernie Rosner recount-ed his experiences during World War II to students last month.

Several sophomore and junior classes gathered in the library on Jan. 25 to listen to Rosner, who was born in 1932 in a small town in Hungary and was raised as an Orthodox Jew.

Rosner told students that the first 12 years of his life were happy, despite the anti-semitic sentiment he and his family were often subjected to.

But a sudden change in his life came on March 19, 1944, when Rosner learned that Nazis had taken control of Hungary, meaning he and his family would not be safe for long.

“The effects were imme- diate and disastrous,” Rosner said. “Anti-Jewish edicts were issued. By mid April, all Jews were required to wear a gold star and by mid May, Jews were herded into a ghetto.”

Rosner, who is now 87, vividly remembers being loaded into a cattle car with his family and being transported to Auschwitz, the location of his first concentration camp. Not many would survive the journey.

“I remember there were at least half a dozen corpses [in the cattle car],” Rosner said.

At Auschwitz, he was separated from his father and later his mother, both of whom he never saw again. Rosner and his 11 year old brother then came across two lines of men.

“I was about two steps past the Nazi soldier when he

grabbed me by the scruff of the neck and shoved me into the [right] line,” Rosner recalled. “The shift from the left line to right line was the difference between being able to live and ending up like the rest of my family.”

That was the last time he saw his brother.

Every day for the next 10 months was a battle of survival for Rosner, who struggled to avoid being sent to gas cham-bers because he kept unkinghis physicals and therefore could not work.

In mid September of 1944, Rosner was able to get trans- ported from the Auschwitz concentration camp to the one in Mauthausen.

“It was known as the most brutal concentration camp,” Rosner said, “but to me it was a lifesaver.”

At Mauthausen, a typical day for 12-year-old Rosner consist- ed of being forced to stand in the freezing cold for hours in nothing but his prison uniform, being fed coffee for breakfast, a cup of greasy liquids for lunch, and a slice of bread for dinner.

“Hunger, cold, daily beat- ings, unsanitary conditions, disease, and almost every other privation known to mankind,” said Rosner, describing the con- ditions. A year later, at age 13 he weighed a mere 52 pounds.

Throughout the horrific conditions Rosner faced, he was able to find solace in his friendship with another survivor in the refugee camp he had been relocated to after being liberated by American soldiers.

“You could not possibly survive the trauma of the camps without a friend to lean on, give support to and receive support from,” Roser said. “I will forever remember the day I saved [my friend’s] life with a ration of bread.”

A chance encounter with an American soldier was the ulti- mate saving grace for Rosner. A soldier named Charlie Merrill formed a bond with 13 year old Rosner and after being sent back to America, he used thenext two years to bring Rosnerto the country and make him a part of his family.

In January 1948, Rosner, then 16, arrived in America to start a new life. Rosner went on to study law at Cornell University and Harvard, and later started a career in law in California.

“After witnessing the break- down of basic ideals of civilization, I was drawn to a profession that upheld values that Nazis so ruthlessly trampled upon,” Rosner said.

For 40 years, he did not talk about his background andexperiences simply because

he didn’t nd it relevant. Aftervisiting the Holocaust museum in 1992, he decided it was time to open up to others.

“I was given access to the log entry of prisoners entering the Mauthausen concentration camps and I found my log entry‘Prisoner 103705’ and a ood- gate of memory and emotion overwhelmed me,” Rosner said.

Rosner later met and befriended Fritz Tubach, the son of a Nazi soldier, and the two decided that as citizens of the United States, they were responsible for their own actions, not those of their fathers.

Rosner and Tubach later published in 2010 a book titled “An Uncommon Friendship:

From Opposite Sides of the Holocaust,” detailing theirexperiences in WWII from twodifferent perspectives.

“[It’s great that] two people with such opposed histories could surmount the walls that could’ve divided but chose toenable a friendship and joinforces to tell what is a warm, and inspiring story,” Rosner said.

Toward the end of the writing process of his book, Rosner met his future wife, Jane, who very quickly became privy to his earlier background.

“In his book, there isn’t a lot of emotion and he tempers it down because that is how he survived,” she said.

Many students who attended Rosner’s speech, which was organized by English teacher Michelle Mascote, were moved by his words.

“It was a really powerful and emotional session with a greatlearning experience for us asstudents,” sophomore Olivia Haley said.

Added junior CaliforniaPiwinski, “I think it was good for us to hear because we are one of the last generations to be able to hear the effects ofthe Holocaust from a rst handsurvivor.”

When asked what he wouldlike students to take away from his story, Rosner said, “Resil- ience of the human spirit and the ability to rise from the ashes.”

Ananya Nag is a news editor for The Californian. As a senior, this is her second year in Newspaper and she served as a reporter last year. Her favorite...

Isaac Oronsky is a senior and third-year newspaper student. He is serving as one of two Managing Editors for The Californian, and is beyond excited to...

sharon Lynch • Aug 27, 2020 at 9:59 am

I grew up in Burton Valley and babysat Bernie’s 3 boys. I remember Bernie whittling popsicle sticks and seeing the number tattoo on his forearm. He told me it happened during the holocaust. I knew it was serious, I felt sad…but did not still fully understand at that time.

As my understanding deepens I think of Bernie and his family, and have often hoped for the best life for him.

i would love the opportunity to re connect with him and his Sons.

Thank you for this lovely article.

Sharon Lynch

Bernies neighbor from Rohrer Drive

2 doors down.

much love