Band department awaits fourth director in four years

A revolving door of band directors requires district music teachers to step in

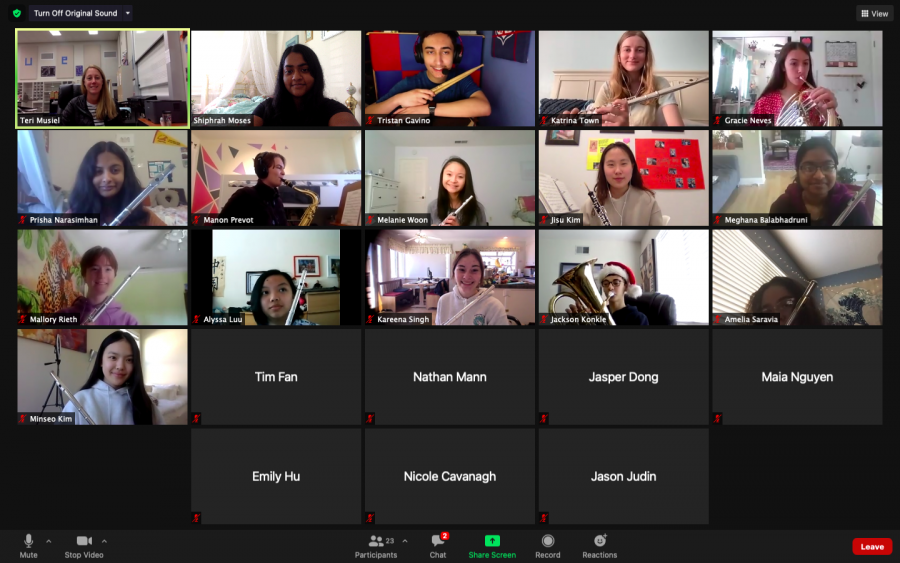

Members of the wind ensemble class pose with their instruments during a recent Zoom class. The class has been taught by Teri Musiel, Dougherty Valley High School’s music teacher, since late March after Cal’s band director Matthew Smith resigned.

When Cal High’s longtime band director Kent Johnson departed in 2019, junior Audrey Luu was upset at the loss of a cherished teacher.

But she never imagined that two years later, the music program would have burned through two more short-lived directors and be left without one in the middle of a pandemic.

Luu, who has played viola in chamber orchestra since she was a freshman, has been taught by three different band directors. Along with Luu, hundreds of other students taking music classes have felt firsthand the effects of having consistently inconsistent leadership over the past few years.

“I feel like the quality of our bands just went down,” senior Huey Chan said, who was responsible for the performance of percussionists on the field as a marching band section leader last year. “There’s so much change that no one can adapt fast enough to meet [the new directors’] standards.”

The most recent director, Matthew Smith, resigned in March, assistant principal Jeffrey Osborn said.

Today, the once vibrant marching band has become a distant memory, strangled by COVID regulations and the lack of a teacher.

In 2018, the program was flourishing under Johnson’s laid-back but respected authority. Johnson had kept the program stable since 2003.

Chan said she remembers Johnson being lenient but fearsome during the rare occasions when they made him angry. She said that made students respect him.

“[Johnson] was also there for the same reason we were, which was to play music with our friends, with that community,” Luu said.

But it wouldn’t last forever. Johnson relocated to Arizona after the end of the 2018-19 school year when his spouse’s company moved, and much of the sense of unity he brought to the band classes would end up leaving with him.

For the 2019-20 school year, Cal hired Michael Samson, previously a middle school orchestra teacher with a degree in music composition. The transition was hard for many students, who said they clashed with Samson’s distinctly different teaching style and mindset.

Chan said Samson took the pre-existing informal hierarchy system within the marching band and made it much more rigid. He established stricter rules, like prohibiting anyone from talking during full ensemble rehearsals, and often said he wanted to make a positive change in the atmosphere.

Samson’s change of pace didn’t bother some students, such as senior Melanie Woon, who was the flute soloist and responsible for conducting the marching band as one of the drum majors during Samson’s year. Efforts to reach Samson were unsuccessful.

“I thought he was a good teacher,” Woon said. “He focused a lot more on the fundamentals and the basics than we had focused on before.”

But Samson’s teaching approach wasn’t the only change for the marching band. Members also grappled with Samson’s administrative assistant and leadership coach, Kelley Ho, who happened to be his girlfriend.

Ho, who was paid by the district, heavily emphasized strong leadership and rules in the marching band, and sometimes came across as intimidating and unapproachable, Chan said.

“No one really knew what her exact job was,” Chan said. “Some of the drum majors weren’t happy about the way they were running things, because a lot of it went against our interest.”

Luu has similar stories about changes Samson made in orchestra, like the increased focus on warm-ups but less practice time, and the introduction of singing their scales. Luu said she didn’t want to detract from Samson’s teaching, but his approach was not her favorite.

“It just felt less fun,” Luu said. “We didn’t want to sit there first thing in the morning and listen to him make us play the same note for 10 minutes.”

While Chan understood Samson’s good intentions for reform, she felt he was too ambitious for the class to keep up.

“We weren’t used to his new way,” Chan said. “The entire marching band was generally less happy and had lower morale.”

Chan said Ho left the program some time before Samson did, but everyone was surprised when Samson ended up leaving as well. He sent a goodbye email to his students after the 2019-20 school year ended virtually, saying he was going to focus on freelance composing and private teaching without citing any specific reasons.

Samson’s exit, in conjunction with the pandemic shutdown, created the perfect storm for the marching band. In the middle of its 2019 winter season, the program was axed.

“In combination with the change of leadership and COVID we weren’t able to have a season,” Woon said.

Members of the band also have found it difficult to maintain their technique. When Samson departed, they didn’t know who to reach out to to borrow larger instruments from school to keep practicing.

Despite the marching band’s hiatus, Woon has been hard at work trying to revive the program with the help of the administration and boosters.

“We are planning to possibly play at graduation, we’re hoping to plan some in-person rehearsals,” Woon said. “We’re going to have to recover from COVID, and bring in incoming classes that haven’t experienced marching yet, so it’s going to be a process.”

The 2020-21 school year would see Smith’s arrival. His time at Cal would be controversial and even more brief than Samson’s. At one point, Smith told orchestra students they would be stopping virtual ensembles, even when students offered to do the editing work independently.

Luu started talking to other students who also had grievances with Smith. After she said he declined their request to discuss how they felt during student support, Luu’s group sent an email on Oct. 19 to Principal Megan Keefer asking to set up a meeting with Smith and an administrator to mediate.

After a few redirections and reschedules, Osborn finally arranged the meeting with Smith and five of the students on Nov, 12, nearly a month later.

“There were definitely some communication style issues that needed to be worked out,” Osborn said. “Some of the expectations were unrealistic for a high school music class, and were among a college-level music theory class instead of a performing class here at high school.”

After the meeting, Luu said she didn’t notice any immediate changes aside from Smith opening up the chat box during Zoom classes. It wasn’t until second semester that Smith started reintroducing virtual ensembles.

“By the time second semester came, it was still not great, but we were kind of complacent at that point,” Luu said. “We expected him to not come back next year.”

So on March 19, when students received an email from Osborn that Smith would no longer be working at Cal and that his position would be filled by members of the school district’s music community, Luu was stunned, but definitely not upset. In fact, she feels the transition has been amazing because of the teachers who stepped in to help.

When Osborn sent out a plea for help after Smith’s resignation, Cal High choir teacher Lori Willis, along with band teachers from Dougherty Valley High, Los Cerros Middle, Diablo Vista Middle, and San Ramon Valley High, responded.

In addition to the classes that they are regularly in charge of at their respective schools, each teacher leads one class that would normally be instructed by the band director. Without them, the band program would have been trapped in a limbo of shifting substitutes until a fourth director is hired next year.

“They have risen to the occasion,” Osborn said. “They are taking on extra students, extra classes, extra work, just for the love of teaching music.”

But the past two years of instability in combination with the COVID-19 pandemic will not be erased that easily. Along with the downfall of the marching band, Luu, Chan, and Woon all have noticed interest in the music program seem to decline over the past few years.

“It’s kind of sad to have seen [marching band] shrink and see less people interested,” Woon said.

Luu said that each time the director changed, more and more students left her orchestra class. She knew some people who left due to Johnson’s departure, and new auditions Samson conducted at the end of his year weeded out more people.

“A lot of it is about the community for us,” Luu said. “If the person who is supposed to be heading that community is so detached from it, so controversial, it doesn’t help make it fun.”

For now, the district’s music teachers will have to suffice. While they tie the fragments of the band program back together, administrators are hard at work trying to hire director number four.

Osborn is working with other administrators to find the most qualified teacher for the job. The position of band director entails teaching five classes, along with the marching band in fall, managing boosters and donations, maintaining and tracking numerous instruments, arranging trips and competitions, and many other duties.

Osborn admits he’s never seen the marching band perform, and that he doesn’t feel he’s qualified to decide who the band director will be. Because of that, he says he wants to hear input from a variety of stakeholders in the district.

“I know the students deserve more than a revolving door of band directors,” Osborn said. “We will find the right qualified candidate and we will hire a new band director for next school year guaranteed.”

Senior Andrew Ma is Editor-in-Chief of The Californian Paper. Now that he is officially geriatric after writing for the paper since freshman year, he is...

Shiphrah Moses is a senior and is the Managing Editor of The Californian. This is her second year as a part of the class and is excited to finally be doing...